Design for Privacy

Many of us rely on technology and “smart” services to provide accessibility and convenience in our everyday lives. For example, devices that allow voice commands to control lighting or other appliances in our homes can significantly improve the accessibility of an interior space. Services that remember our log-in or purchasing information can make it much easier to access those services on a regular basis. However, the use of these services come with the cost and associated risk of sharing personal information online. Those of us who can benefit most from smart services, including persons with disabilities and persons who are aging, are often the most vulnerable to the misuse of private information - for example, through denial of medical insurance, jobs and services, or fraud.

Putting control of online personal privacy into the hands of the user is an important aspect of inclusive design. Many people avoid using particular services (for example, online banking) due to fear of misuse of their personal information. Too often these choices are based on a lack of knowledge of how our personal information is being used and/or of how we can protect it. And, even when a service explicitly describes its privacy policy, it is often presented in legalese or other language that is complicated or vague. Many services do not allow a sufficient level of control over the user’s privacy.

The following art installation by Dima Yarovinsky visualizes lengthy “terms of service” agreements from popular social apps—including Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and Tinder—in his project, titled I Agree. In most cases, users either accept these terms without reading them or abandon the service entirely.

Figure 1: Dima Yarovinsky - I Agree: a visualization of lengthy “terms of service” agreements from popular social apps including Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and Tinder

Image courtesy of Designboom

Be transparent and clear

Designing services that have clear, transparent and understandable terms of use and privacy policies can help to educate people about their digital privacy, foster a sense of entitlement to that privacy, and facilitate more informed choices. A good design should communicate privacy information by using plain and simple language in order to maximize the ability of users to comprehend how, where and by whom their personal information is being used. Design should also provide users with practical and easy to access means to give, deny or revoke their consent to share their data. In addition, the default privacy setting should be set with a high level of privacy, allowing the user to opt in to sharing information rather than having to opt out.

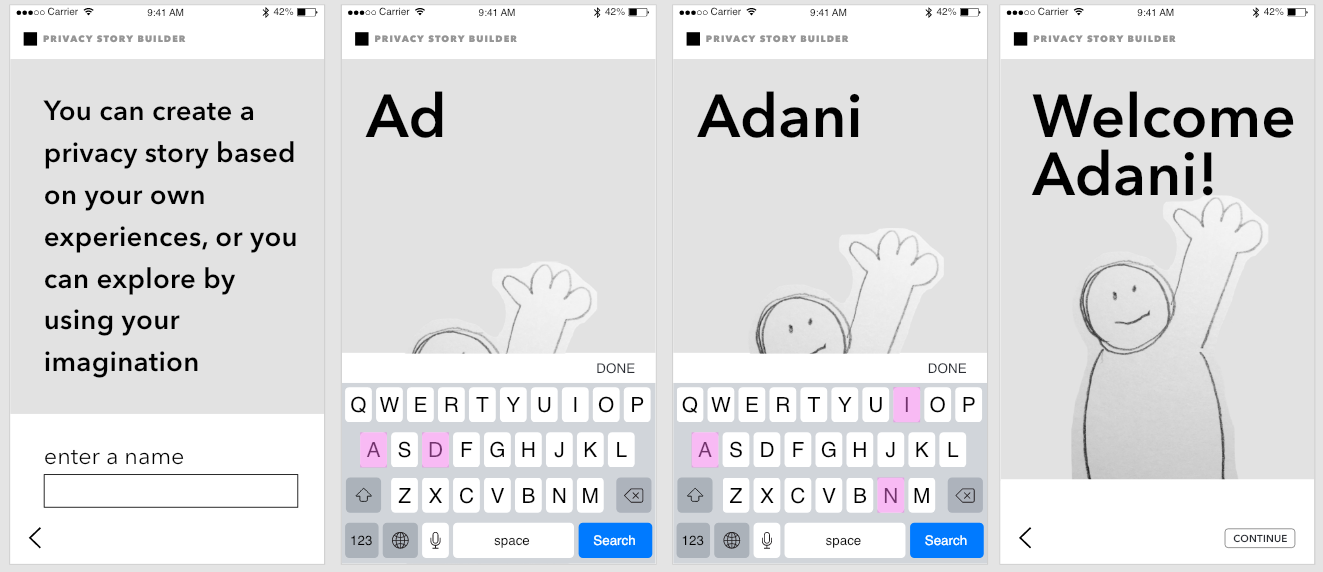

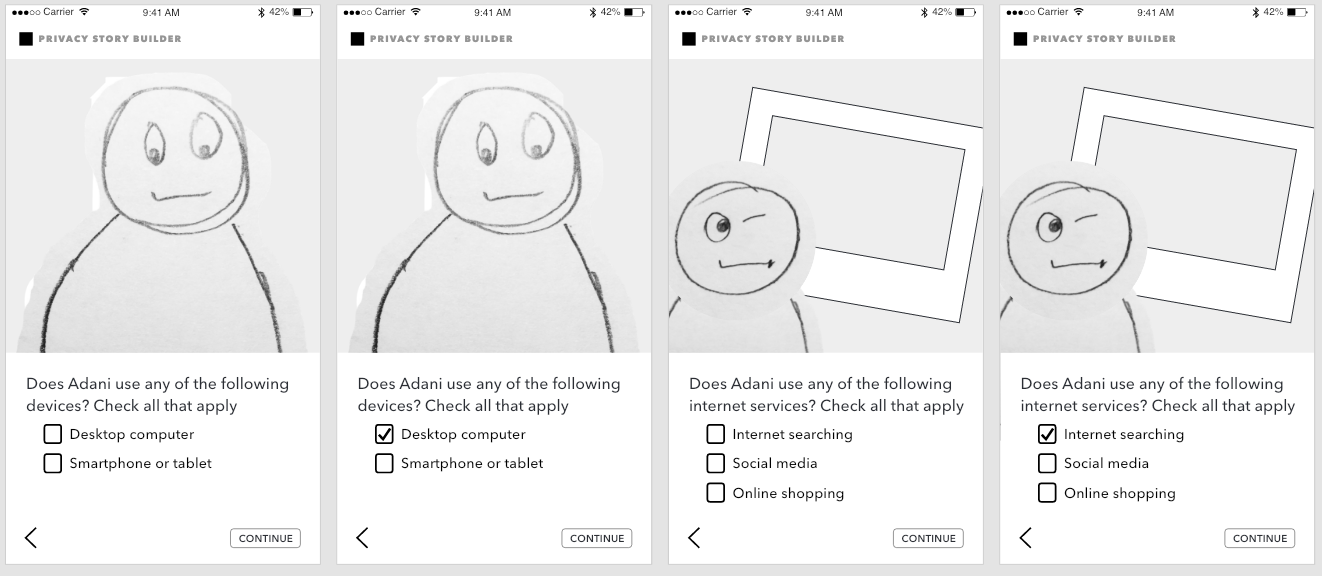

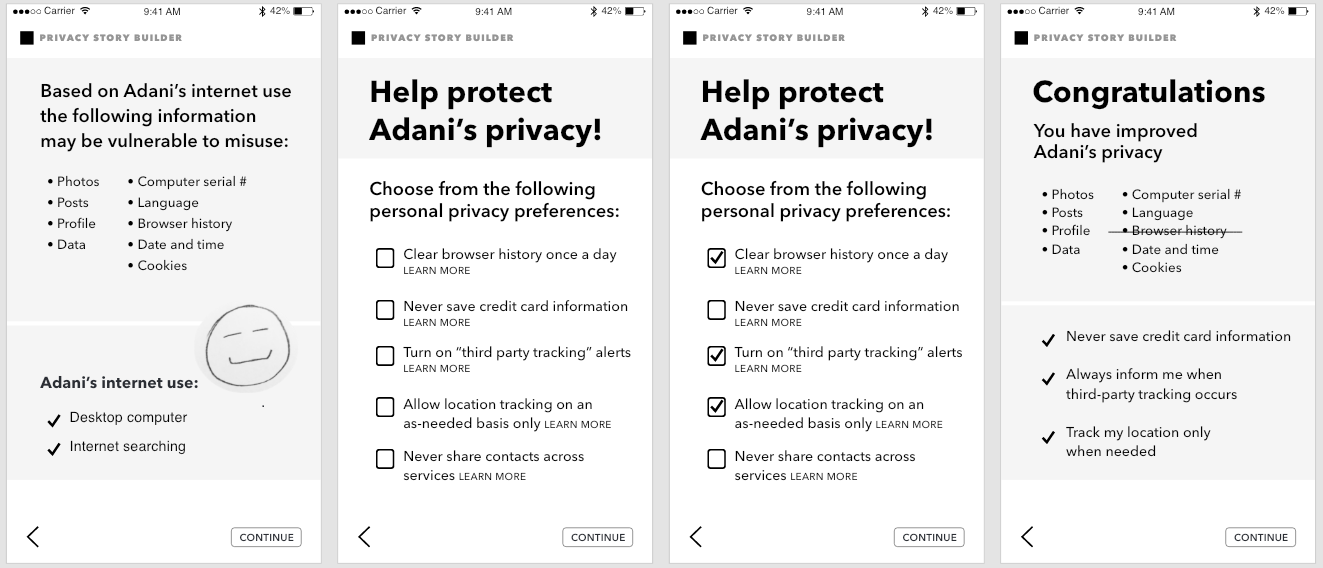

Figure 2: Story builder tool - introduction screenshots

Figure 3: Story builder tool - internet use screenshots

Figure 4: Story builder tool - privacy options screenshots

Minimize collecting personal information

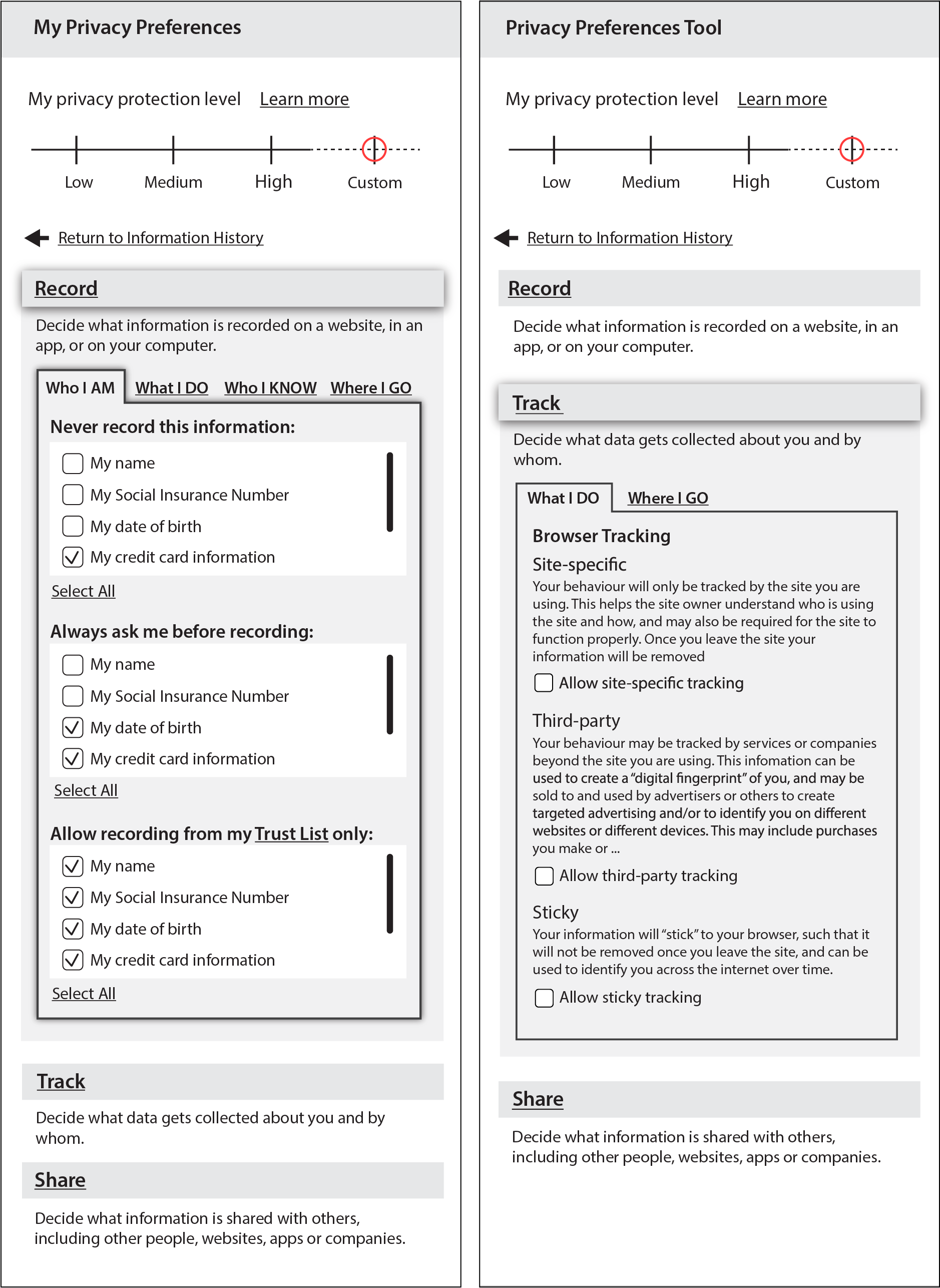

Data minimization is another aspect that should be considered when collecting personal information. When designing for privacy, we should always consider why we need a specific type of personal information and if there are other ways of achieving that purpose without having to collect the data. Design for adaptability and flexibility An individual should be able to manage the use of their personal data and for their own purposes. Users must be able to personalize their experience to match not only the task at hand, but also to match their acceptable level of risk. Providing a way for users to weigh the risks and benefits of sharing their personal information online is an important aspect of designing for privacy. Users should be able to easily adjust their privacy preferences in different contexts to be able to achieve their goals without compromising their privacy. Designing and implementing segmented privacy policies that can be accepted by the user in part or in whole can also help.

Figure 5: An example of an advanced privacy preferences tool allowing the custom setting of personal privacy preferences.

Support information portability

Users should be in control of where they want to store their information. A good design should enable portability of personal information among different services and allow users to easily access their data and move it to their desired location either online or offline. The output should be interoperable and easily work with common systems and services, so users are not required to install or purchase specific programs or software in order to access their information. Another way to enable data portability is to include means of creating trust lists or circles of trusts of services or people with which to share personal information.

Services should also include an option to permanently delete the user information. This is specifically important when users want to move their information from one service to another and terminate their use of a service.

By embedding privacy into design from the start, it becomes possible for usability and privacy to co-exist. Designing for privacy foments an innovative space in which we can meet the challenge to develop exciting new solutions.

Resources

- Privacy by Design

- International Council on Global Privacy and Security by Design

- The Electronic Frontier Foundation

- Me and My Shadow Project

- Projects by If - data permissions catalog

- The Platform for Privacy Preferences Project (W3C)

- Designing a Privacy Preference Specification Interface - A Case Study. Cranor, L.F.

- User Interfaces for Privacy Agents. Cranor, L.F., Guduru, P. and Arjula, M.

- Usable Privacy Policy Project

- The Privacy Bird