The Three Dimensions of Inclusive Design: Part One

This work “The Three Dimensions of Inclusive Design: Part One”, is a reproduction of “The Three Dimensions of Inclusive Design: Part One” by Jutta Treviranus, used under CC BY-NC 4.0. This is the first part of a three part blog that describes a guiding framework for inclusive design in a digitally transformed and increasingly connected world. Part Two can be found here. Part Three can be found here.

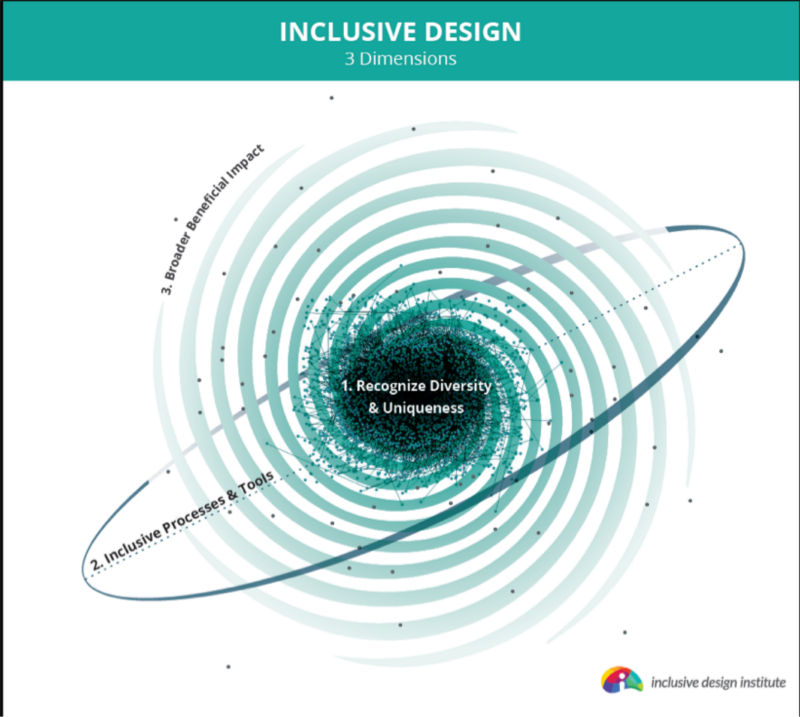

The three dimensions of the framework are:

Recognize, respect, and design for human uniqueness and variability.

Use inclusive, open & transparent processes, and co-design with people who have a diversity of perspectives, including people that can’t use or have difficulty using the current designs.

Realize that you are designing in a complex adaptive system.

Figure 1: Handprints

With the help of my team at the Inclusive Design Research Centre and our amazing global community I have tried to develop a guiding framework for inclusive design, suitable for a digitally transformed and increasingly connected context. It doesn’t lay out testable criteria, or an ordered checklist, because inclusive design is about diversity, variability and complexity.

Figure 2: The framework is a trellis that supports organic growth

It is not a set of static structures that assist in engineering a solution, because the complex adaptive system that is our current society is a domain where solutions can no longer be engineered but approaches must be grown, and investment in a fix for some creates greater barriers for others. The framework is intended to be more like a trellis that supports organic growth and provides a foundation from which to innovate and evolve. It has emerged, evolved, been tested, and refined over the 25-year history of our centre, in dozens of global initiatives.

The three dimensions of the framework are:

Recognize, respect, and design for human uniqueness and variability.

Use inclusive, open & transparent processes, and co-design with people who have a diversity of perspectives, including people that can’t use or have difficulty using the current designs.

Realize that you are designing in a complex adaptive system.

Figure 3: The three dimensions of inclusive design.

I will discuss each dimension in turn in this three-part blog. Part Two can be found here, and Part Three can be found here.

Human Uniqueness

The first dimension of the framework is to recognize the uniqueness of each individual. We are each an irreducible and evolving complex adaptive system of characteristics and needs. This uniqueness and wild, organic diversity has been inconvenient when it comes to designing products, communication, environments, or policies. It defies mass production, mass marketing, mass communication, mass education, as well as simple and straightforward public policies.

Throughout civilization there have been attempts to corral and tame this diversity and complexity and find ways to deal with people as a more manageable, simple, and homogeneous mass. The more egregious attempts have employed violence, genocide, exclusion, othering, shaming, shunning and informal or formal discriminatory practices. Other strategies have been coercion, indoctrination, acculturation, breeding, propaganda and schooling. In our quest for knowledge or research and in our governance strategies we have reduced people into simple numbers that ignore this diversity and complexity. Through our laws, policing and penal systems we attempt to contain the edges of this diversity that are deemed more negative, but we have also institutionalized systems that either deny or suppress the harmless and beneficial aspects of this diversity, adaptation and complexity. If we can’t eliminate certain diversities we have sequestered and incarcerated people in camps, ghettos, “mad houses,” and specialized institutions for “deviants.” This aversion to diversity is both damaging to individuals and dangerous to our societies. (I would contend, but have not gathered enough evidence to assert, that the suppression of the positive aspects of our diversity contributes to the expression of the more negative aspects of our diversity.)

Let’s imagine for a moment that the supposed utopia of a homogeneous mono-culture of ideal human beings were even achievable. Yes, manufacturers could produce a single simple product and market it to the entire customer base. Policymakers and researchers could easily predict behaviors and design policies to accommodate these behaviors. We could communicate a message in a single form and know that it is understood and received by everyone in our mono-culture. The requirements of our built environment would be straightforward and predictable. We would obviate empathy because everyone would be like us. But we would stagnate as a species as there would be no alternative ways of being to evolve toward. Any threat, such as a disease or a natural disaster would fell our society, as there would be no variability in immunity, or alternative responses to the threat. We would have a blinkered and limited perspective of our world and fail to see both all the wondrous but also the possibly dangerous edges. We would end innovation as there would be no disruptive and resourceful new responses emerging to challenges and dissonance. Yes, we could be comfortable and complacent, but we would not move or grow, individually as a person or collectively as a society.

Relaxed Selection

You might ask, isn’t it beneficial to prune the diversity by eliminating weaknesses and “deficits” and thereby strengthening the species? Isn’t evolving and advancing our species assisted by Darwinian survival of the fittest? Some people claim we can do this humanely through genetic engineering and doctor assisted suicide. According to Terrence Deacon, if this were the case we would not have developed language. If we trace the periods in our history as a species when we have made the greatest advances, it is at the times when we have had the benefit of relaxed selection. This means an absence of the pressures of survival of the fittest. This is when diversity can thrive. We have come to see the pivotal role that the complex adaptive social system plays in evolution. Variability and diversity, especially what we deem weaknesses and deficits, prompts the system as a whole to evolve and gain resourcefulness. (There are endless modern-day examples of this phenomena that include email, voice recognition, the telephone and aspects of the Web that make it successful).

Perfection and Change

Humans are a social species, we have become ever more entangled and connected. To advance as a species we must consider not only the isolated representatives of the species but the enmeshed collective system as a whole. We need fragility, weaknesses and gaps to enable change. As Leonard Cohen sang, “There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.” When we near ideas of perfection, when systems become established, complacent and entrenched, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to change. Take systems of education in regions where education is institutionalized and revered. Take policies and practices that have become so habitual that they are unconscious. It requires major disruptions, or incidents of “creative destruction” to prompt the established and conventional to appropriately respond to a changing world. But a system, such as a team, that has diversity and variability within it and works to make room for and truly include this diversity can responsively change, remains dynamic, has enough collective perspectives to see the entire periphery to avoid and respond to threats and to notice promising opportunities. Such a system can also judge and test potential actions more thoroughly.

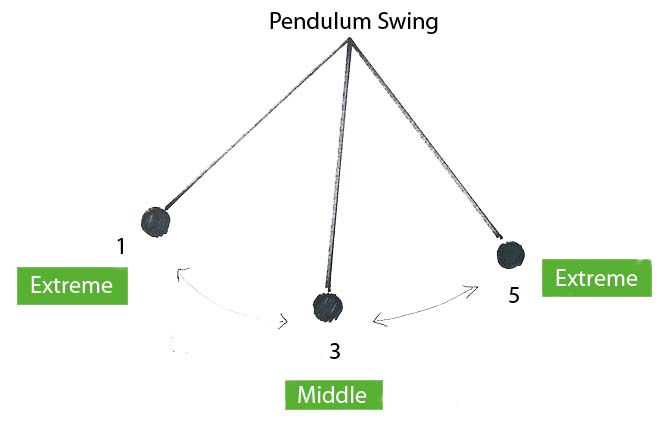

Such a system has far more choices. It is better at resisting polarization because there are more than two powerful viewpoints. Paradoxically, if you have a platform with a huge spread of positions or perspectives you have greater equilibrium and can resist the swing of the pendulum between two extremes. This ensures that a political pendulum never swings too far into any extreme direction.

Figure 4: Pendulum Swing.

Enlightened Self-Interest

As a society we need people who lead in facing challenges (that we often characterize as deficits and weaknesses), to stretch our boundaries as a society. We need these involuntary pioneers to not only stretch our boundaries in designing our environment, policies and products, but also our boundaries regarding the qualities we have come to see as our humanity. It is a bad day for our species when it becomes obvious that elephants, whales and dolphins surpass us in these “human” qualities of empathy, kindness and social cohesion. Every human, and every society will face challenges. As our mothers would remind us: “what goes around, comes around.” Karma is not mystical, it is logical. If we help to develop a society that responds respectfully to human variability, there will come a time when we ourselves benefit from that respect. If you prefer, this can be seen as a form of selfishness. We can also see it as enlightened self-interest. It is an investment in our long-term interests and the interests of our children. It is a way of preparing for the unpredictable and the unplanned.

Not Charity

I can argue that both Ayn Rand’s and Adam Smith’s views of the virtues of self-interest are too reductionist, impoverished and short-sighted. They fail to consider our complex, adaptive and entangled world and our inter-dependencies. To be clear, I’m not promoting charity. Charity, where the powerful, privileged and well-resourced deign to assist and give of their wealth to the less privileged, less fortunate and weaker, sets up an untenable power imbalance. It reinforces the superiority of the giver and the inferiority and expected indebtedness of the receiver. It is also vulnerable to “charity fatigue.” The receiver or supplicant must compete with many other possible receivers in a race to the bottom. Each potential recipient of charity competes for the position of the most pitiable. This competition normalizes the horrors of inequity. It is a vicious cycle and can only be a temporary Band-aid in a dire situation while we address the underlying causes.

What I’m recommending is a society or social system that is designed to respect and include diversity and human variability at every nested level. We need a society where it is possible for people, with the full range of human difference, to participate and contribute.

Responsible Designers

Designers play an ever more important role in this as all fields of design and also design thinking are ascending and applied in more and more contexts. However, to apply this dimension of inclusive design requires unlearning many established conventions of design. Designers are taught to reduce and ignore complexity and diversity by creating representative persona of the typical or average user. As Todd Rose eloquently argues in his book The End of Average, there is no average person. Average is an artificial construct. There is not even an average us, we each vary from context to context, from goal to goal. Designers reduce contextual complexity by working in sterile and isolated labs. However, the design will not be applied in sterile and isolated conditions. Design research works toward finding one winning design that meets the needs of the largest customer base. This excludes anyone that is different.

Approaches at the Margins

Even the design practices that are intended to address the needs of people at the margins of our society, people who are viewed as different, often employ practices that ignore diversity. For example, we have propagated the notion that there is a one-size-fits-all version of accessibility for people who experience disabilities. However, the single defining characteristic of disability is difference — sufficient difference from the norm that things are not made or designed for you. In fact, people who experience disabilities are even more diverse than people who can use standard designs. They also have less degrees of freedom to adapt to a design that doesn’t fit well. Sorting and filtering people into categories and classifications based on a specific characteristic, such as a medical diagnosis, and designing for that category is another way of taming diversity. However, this leaves people falling through the cracks and stranded at the edges.

The Qualities of the Digital and the Networked

So, what am I suggesting designers do? I’m suggesting that we design to include diversity by leveraging the affordances that our digitally transformed and connected world provides us; to offer one-size-fits-one configurations that can be optimized to each user and stretch out to the edges of our human scatter-plot of needs and characteristics. The digital and networked presents many challenges but it also presents some powerful qualities and tools that make it easier to respect and optimally design for diversity and complexity. Unlike a door to a building that demands compromises and choices regarding how people enter, in a digital system we can present a different door configuration to each person, even if they are entering as a group, and going to the same destination. Using such things as style sheets, personalization, adaptive and responsive design, the door can morph and adapt to the needs of each visitor.

As far as adaptation and personalization, I need to add three provisos.

Not Segregated or Separate

First, the one-size-fits-one design cannot be separate or segregated. If it is separate from the general market it will cost more. If it is designed separately from the standard application, it will be less interoperable. It will require special training and separate maintenance. Interoperability is a critical factor in the entangled, quickly evolving, complex networks that we depend upon, and a separate solution soon becomes orphaned and incompatible.

Enabling Smarter People

Second, if smarts are used to learn what each individual requires, we need to make sure that the person directs and gains the insight. The intelligence we gather should make the person smarter about their unique needs, rather than, or as well as, the machine smarter about how to adapt. This requires transparency regarding choices made and the reasons for the choices.

Optimal Fit

Thirdly, one-size-fits-one implies an optimal fit for the goal, it doesn’t necessarily mean a comfortable fit. If the goal is to learn, then the optimal fit will provide a challenge that is at the limits of achievement. The echo-chambers, and cushioning from alternative views, created by personalized media and news is not an optimal fit and does not serve to inform or present an accurate view of the world. An optimal fit in this domain would be to provide language and presentation choices that can be personalized to the individual’s needs so that more can be understood. It means translating currently foreign viewpoints, so they can be understood by strangers. Academics, scholars and researchers need to learn to use this form of design so that knowledge can be more democratically shared. Inclusive personalization builds bridges across differences and reduces fragmentation.

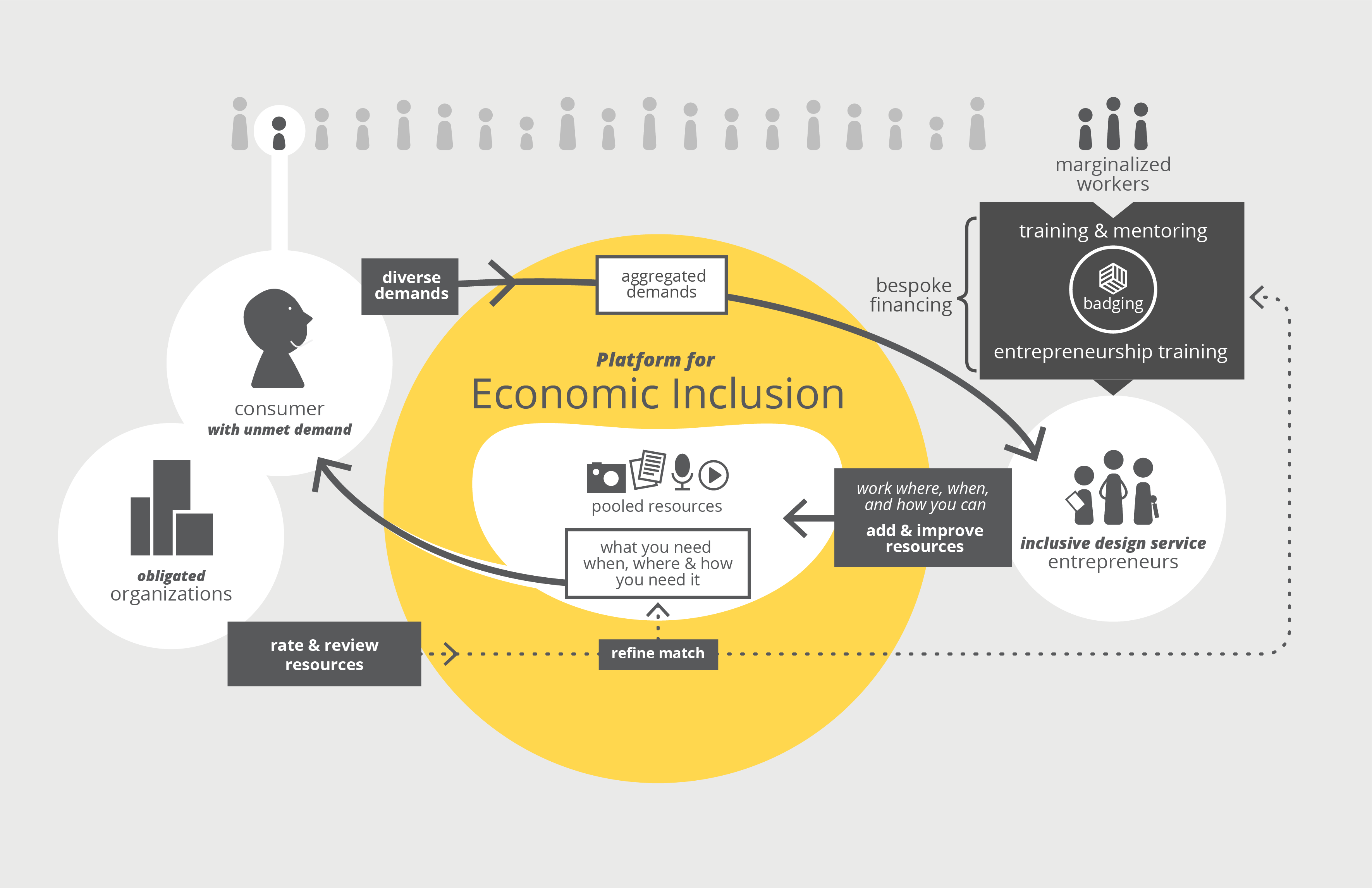

Pooling, Sharing and Matching Needs Over a Network

Figure 5: The use of a network platform to address our diverse unmet needs

A networked system makes it possible to share and pool resources so that we can create a wealth of variants to match the full diversity of needs. We can reach out across networks to find diverse innovators that can fill gaps and unmet demands. A networked community can help find a match, augment or translate designs so that everyone has choices that optimally meet their diverse and variable personal requirements.

Diversity is our most valuable asset. Inclusion is our biggest challenge. Taking up the challenge will make our design better, and the human community we design with better.