The Three Dimensions of Inclusive Design: Part Two

This work “The Three Dimensions of Inclusive Design: Part Two”, is a reproduction of “The Three Dimensions of Inclusive Design, Part Two” by Jutta Treviranus, used under CC BY-NC 4.0. This is the second part of a three part blog that describes a guiding framework for inclusive design in a digitally transformed and increasingly connected world. Part One can be found here. Part Three can be found here.

The three dimensions of the framework are:

Recognize, respect, and design for human uniqueness and variability.

Use inclusive, open & transparent processes, and co-design with people who have a diversity of perspectives, including people that can’t use or have difficulty using the current designs.

Realize that you are designing in a complex adaptive system.

Figure 1: Co-designing in a diverse team

The Lessons of Unrecognized Technology Pioneers

Design is an awesome responsibility. There are many things that can go wrong or ways it can go “sideways.” To avoid doing something embarrassing or dangerous requires more than creativity and a sense of aesthetics. It requires a keen understanding of all the people that will use the design, their goals, and their variable contexts. Design is an especially daunting responsibility when you are designing things that are essential to someone, or designing things that require a significant personal investment from the user.

I came to this realization many years ago when I started working with some of the invisible and unsung technology pioneers. These are the individuals that have been labeled “extreme users” or “edge users.” They have no choice but to risk the frontiers of technology design, and what they personally invest is profound and deep.

The pioneers I worked with included technically courageous kids that learned a complex code during kindergarten, so they could talk and communicate (in this case it was a form of Morse code because it only took the timing of the one voluntary action they could reliably control). They included a hugely innovative and resourceful couple that learned a new means of writing almost monthly because the husband gradually lost functions as a debilitating progressive illness took its course. They also included a brilliant math student that had the patience to struggle with the inexcusably bad translations of math notation to synthetic speech, so she could obtain a math doctorate without sight. Over my 38 years in this field I have had the personal privilege to work with many more. It is working with these technical pioneers that has taught me the most about the process of design.

The Responsibility of User Investments in Technology Designs

Most of us can survive without the majority of the technologies we use. If the technologies stopped working, it is no doubt that we would be inconvenienced. It might be a shock to be forced to travel to see someone because our cell phone isn’t working, to write with a pen or pencil because our computer is misbehaving, to go to a shop to buy the things we need because the Website is down, to pick up a book or visit a library to find some information we need; but we would get by.

For a growing group of people, the loss of the use of certain technologies means you have no way to talk, no way to write, no way to travel or move about, possibly no hands or legs, or no way to see, or hear, or understand. Relying on technology for these individuals has always meant a deeply personal and intimate relationship, akin to most people’s current relationships with smart phones or glasses.

This also means that the design that is available to you (because often there are very limited choices, if there are any choices) requires a significant personal investment. If the technology is to fulfill its role it needs to become habituated and its operation needs to become largely unconscious or automatic. Just as we are not aware of moving our tongue, mouth and breathing apparatus when we speak, you can’t be worried about the mechanics of finding and selecting a word to communicate when you use a communication device. It interrupts the flow and the very purpose of communication.

It takes a huge training investment to get to that automatic stage of use. You don’t want to have to learn to talk, write, walk, or read all over again too many times in your life. These are individuals that have many other barriers to face on a daily basis and for whom time and energy is an overspent precious commodity. It behooves us to create the very best personal fit and not require these individuals to unnecessarily squander precious time in struggling with and trying to decipher the interface/interaction/experience design.

Impossible Understanding

One of the first lessons I learned is that no amount of background research and statistics; no persona (however well researched, fulsome, evocative, and motivating); and, no empathy exercises or disability simulations; can ever teach you enough about the very personal and unique requirements and characteristics these individuals bring. It is a shameful conceit to suggest that you are an expert, or that you have more knowledge and insight, it is even hubris to suggest that you really understand. You cannot understand until you have no option but to live it. Even if that were to happen, it won’t be the same experience.

Inverse Effects

One of the distressing phenomena I observed during my career was the degree to which excelling in the respected design methods often led to worse design for the individuals that most depended on a good design. The more the designers engaged in rigorous research, or observation behind one-way mirrors, or focus groups with token representatives of high incidence disability groups, the more the designers failed to ‘get’ these pioneers and what was needed in the design. It was almost like the research and rigor was a shield to really understanding, while at the same time bolstering professional stature and distance.

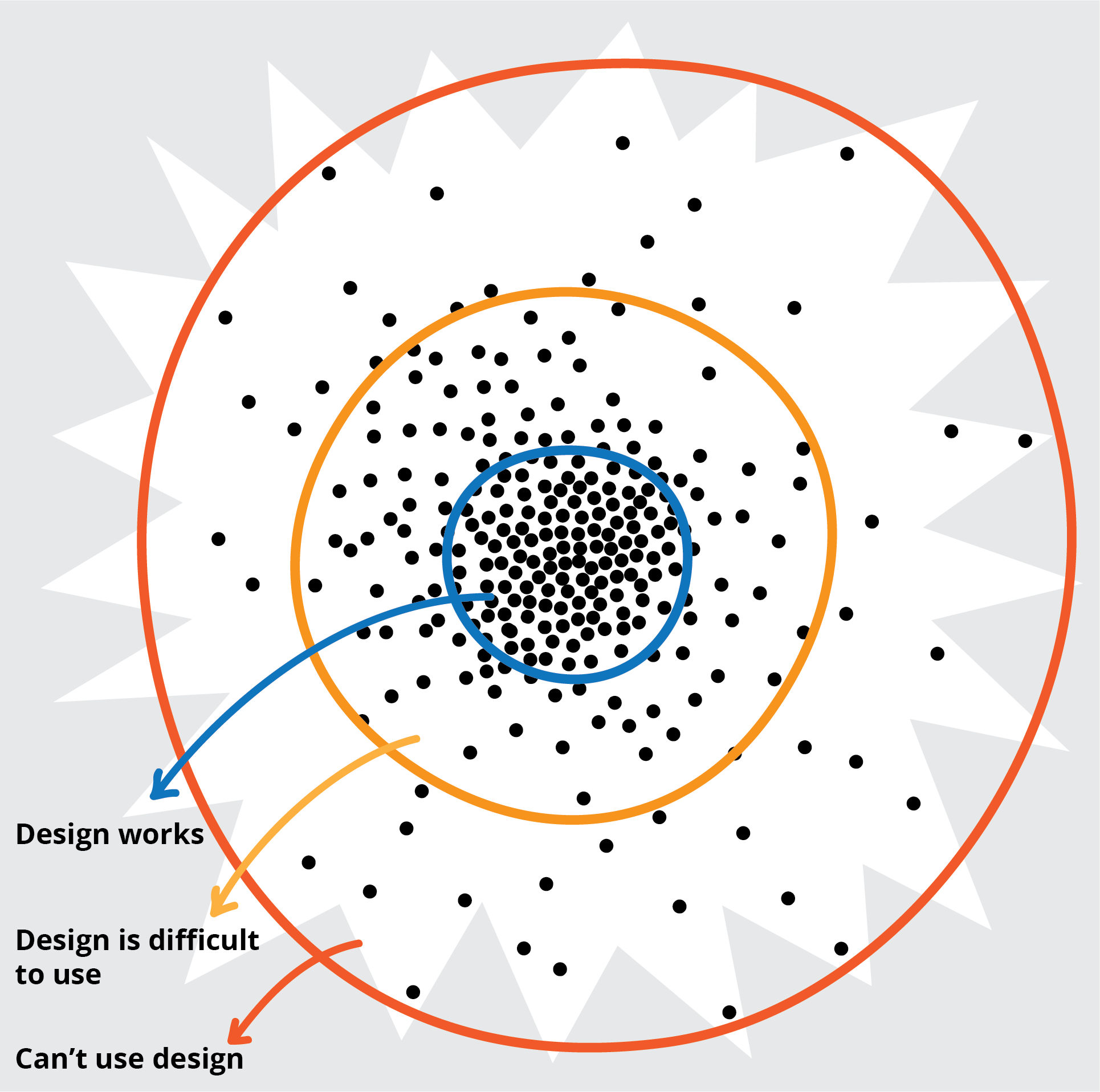

Figure 2: Overwhelmed by the mean

The larger the data set and the greater the power of the statistics, the more likely the unique needs of these pioneers would be lost or overpowered. It often became a tug of war between a design that stretched to where the edge user needed it versus a design backed by the research data — which would lead you away from the edge and toward the mean. Even the more creative design practices that involved an empathy cycle accompanied by ideation or brainstorming often landed on a design that completely missed the mark. While the designers could step out of their own assumptions and preconceptions, it didn’t necessarily mean they could step into the perspective of the edge user.

Authentic Expertise

This led me to the conviction that we need to recruit the most relevant and authentic expertise to the design team, namely the edge users or pioneers themselves. Not as research participants and subjects of study and analysis, but as full-fledged design team members, or co-designers. Not just during “empathy” and “user testing” stages, but throughout all design and development phases. We came to realize that “nothing about us without us” was not just a social justice mantra but a good design practice.

Co-design for the Mainstream

You might say this is great for design that is specifically about people with disabilities, or people who face literacy, aging, cultural or geographic barriers to access; what does this have to do with design in general? How is this relevant to mainstream user experience design?

During our 25-year history my team has employed co-design with edge users and edge scenarios in many design projects that are not directly connected to people with disabilities, whether it is designing better learning management system user experiences, restructuring a government ministry, rethinking what a museum experience should be, planning better emergency procedures, helping to organize more effective transportation systems, working towards more foolproof voting systems, creating more successful open source communities, or designing more effective schools. Through this process we were able to verify Scott Page’s findings that the best planning, prediction, risk aversion and innovation happens when you bring together the broadest range of diverse perspectives. Scott has termed this the “diversity bonus.” Our team, the broader community, our partners, and the graduate program I launched are organized around this insight. At a basic level we don’t separate designers, researchers, developers and quality assurance people. They all work together. But also, the people that fill those roles bring the richest variety of perspectives we can muster. However, you cannot invite all possible users or their representative perspectives into your design teams.

People who can’t use or have difficulty using a design

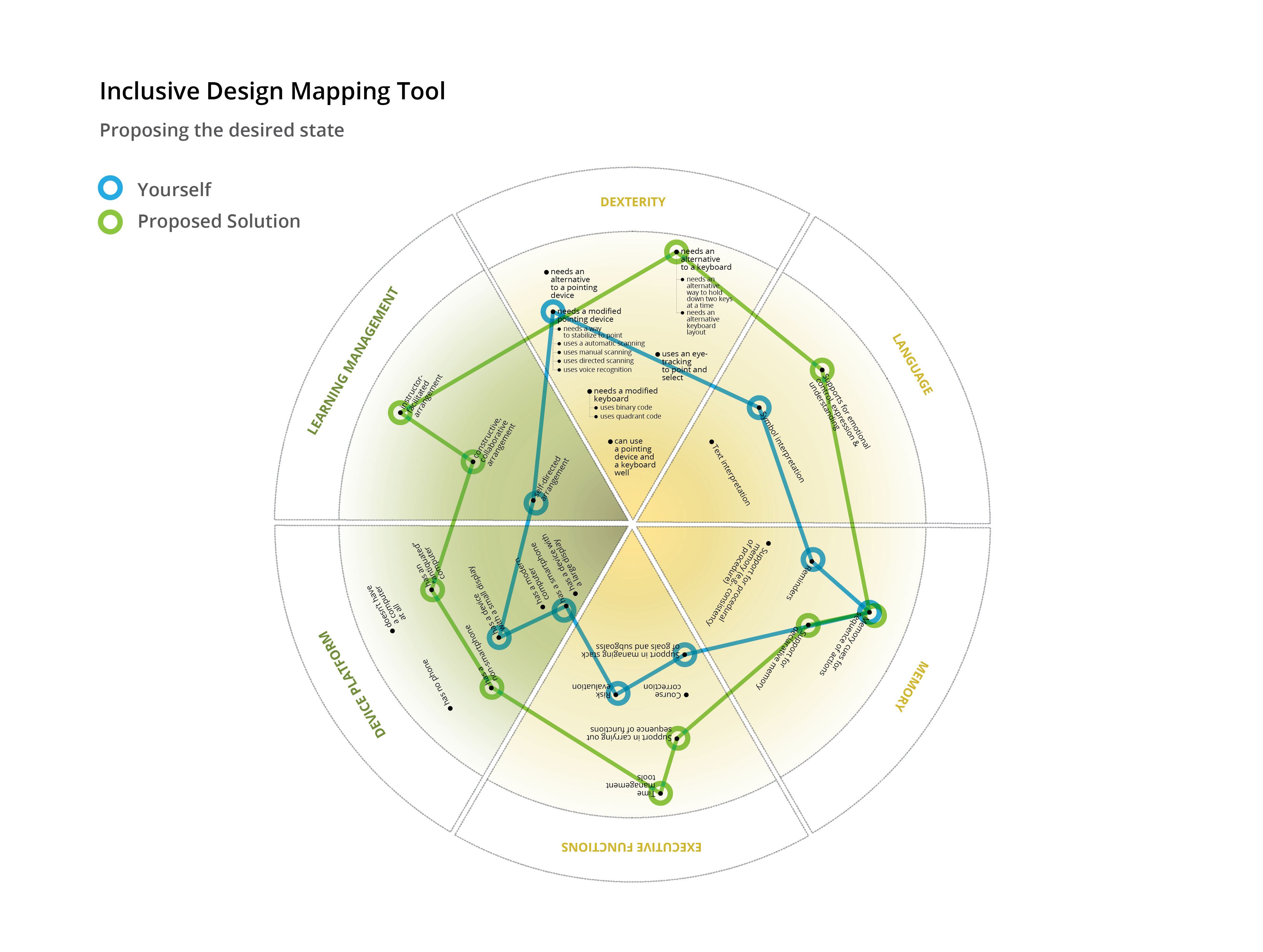

Figure 3: The Co-designers

What we have discovered is that it is predominantly the edge users that contribute the most relevant, innovative, insightful and grounded perspectives to a diverse design team. To them, design isn’t abstract, it is essential and real. These edge users are also less likely to validate and defend a current design that doesn’t meet their needs. This led me to the obvious realization that if you want innovation or even design improvement, the best people to have at the design table are people that have difficulty with a current design or can’t use the current design. They are not invested in keeping the current design and they will stretch or expand your design further.

Earning Trust

However, genuinely and meaningfully engaging edge users in your design process is not an easy feat. With many communities you have to overcome a justifiable trust barrier. Many communities have been burned by exploitative researchers who come to verify their preconceptions. Ask any indigenous community regarding this experience. Or the community has been disillusioned and disappointed by entrepreneurs who feel they have found a solution to a perceived problem, and the experience feels more like the entrepreneurs have identified a nail for their hammer. Many other edge users have consultation fatigue because they have made the rounds as token representatives, so that a box can be checked on the equity and diversity policy checklist once all the important design decisions have already been made. It takes humility, respect, clear terms of commitment, and unwavering transparency to earn this trust.

Inclusive Design Methods and Tools

Another practical issue is that most design tools and activities are predominantly visual and spatial, whether it is the use of sticky notes, the various wire-frame options, mind maps or prototyping tools. If you want to include someone that relies on sound and/or touch, you must thoughtfully and consistently translate, or find alternatives. Most of these tools also require dexterity and manual manipulation to participate. We have played with many less traditional strategies but frequently need to resort to thoughtful teamwork as a fallback. At minimum, we document every design decision, the rationale, and the remaining questions in an accessible digital format such as our Wiki.

Essential Role of Open

Openness and transparency are essential tenets of inclusive design. Proprietary, closed systems always exclude and prevent interoperability. They also prevent extensibility which stunts the growth of knowledge and the integration of diverse perspectives.

Designing the “Table”

We have a commitment to continually ask, who are we missing from the “table” and how can we design our “table” (a.k.a. design process) so that it is more inclusive, and so we arrive at designs that bring about change. We find that the hardest aspects to redesign are not the physical factors, but the presumptions, assumptions and conventions brought by the institutions, organizations and expert designers we engage. People easily slide into traditional scripts and hierarchies and we need to regularly re-calibrate. Designing the structures that guide the process, so that the individual strengths of the design team members are engaged and produce more than the sum of the parts, is often harder than arriving at the brilliant design. The ability to both give and receive truly constructive critique is a valuable group skill. Willingness to take risks and learn from failures, early and often is also a fruitful strategy. A well-functioning and diverse design team is a wondrous, energizing thing that deserves careful maintenance.

A Worthwhile Investment and Smart Strategy

Respectful, inclusive co-design takes a little longer initially but is a valuable investment in the long run. We have confirmed, what others have observed, that the resulting design is less brittle, easier to update, requires fewer accessibility patches, fewer service calls, shorter training, and generally lasts longer.

If you have a complex problem that requires community adoption and participation, addressing the edge scenario is often the best design strategy. For example, if you want to design a smart, sustainable neighborhood in a city where the citizenry distrusts your motives and your plans for managing data, addressing the needs of the individuals that can benefit the most from smart services but are also most vulnerable to data abuse and misuse is a strategically fruitful place to start. This might include engaging people who are blind in designing smart intersections, or people with episodic health issues in designing emergency services, for example. In both cases it is critical that the data remains private and secure. If the data protections are designed to safeguard the people most vulnerable to data abuse, the protections are more likely to meet the needs of the rest of the citizenry. Innovative services for people who can benefit from them the most will produce compelling examples that inspire further engagement. This will work far better than addressing the needs of the average citizen who has less compelling reasons to require smart services, and for whom data privacy threats are more theoretical. If you focus on the design for the majority first, you will need to address the edge scenarios soon enough and your design will lack the flexibility to stretch, so you will need to “bolt on” provisional approaches, which will make your design less sustainable.

Mapping Success

Figure 4: Inclusive Design Mapping Tool

Our criteria for a truly successful design is a design that reaches the edge requirements that we collectively identify within the co-design team. If you reach the edge, the design will also work better for the center. It will be more flexible and generous. If you design with the edge user, someone who isn’t an edge user will have more configuration choices. They don’t need to abandon your design when their needs, goals and contexts change. We often use an inclusive mapping tool to track our progress. We design in short, iterative, full cycles that produce testable functionality as early as possible. Reaching the edges doesn’t happen in the first go-round, but we strive to address more and more requirements and scenarios in each iteration.

Planning Using a Virtuous Tornado

Because we are guided and grounded by the co-designers, and engage in iterative cycles, our process confounds project planners who like linear logic models, and require Gantt or Pert charts to closely track progress. We believe our process is better suited to the quickly changing context of our current society. Who could have predicted the current political and technical situation two years ago in a linear logic model and charted it in a detailed Gantt chart?

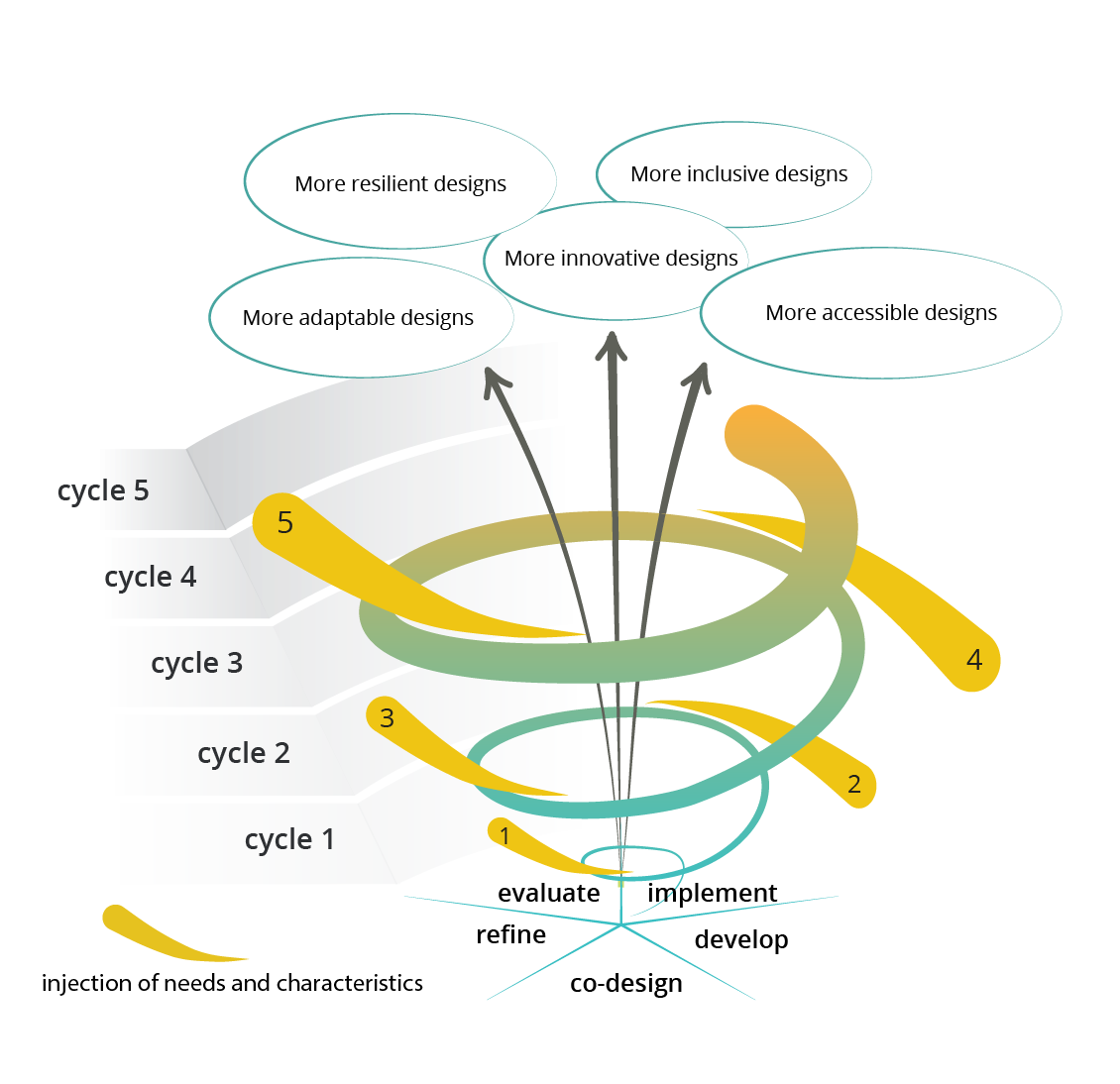

Figure 5: The Virtuous Tornado

We have developed a process we call our “virtuous tornado,” adding more functional requirements and use scenarios at each cycle to expand the design. This way we remain responsive and agile and make more relevant progress that will have greater impact in the long run. Because we don’t iterate toward a single solution but toward a system that can provide an optimal configuration for each user, what we design is more dynamically resilient.

Lasting Change and the Inclusively Designed Process

Many of today’s problems are too complex, people are too diverse, and the context is moving too fast to design a definitive fix or solution. Investment in a definitive fix leads us to ignore the changes, deny the complexity, and exclude the diversity. Inclusive design begins with no predetermined end point and no generalized success criteria but arrives at greater innovation, flexibility, and general usability. Employing an inclusively designed process will achieve a more lasting and productive change than a checklist of design criteria. Inviting the unrecognized technical pioneers to the design table is a gift that keeps on giving.